When the Bread They Have Cast on the Waters Comes Floating Back: Gordon Shadrach & Kachelle Knowles

03/23/2023-04/27/2023

When the Bread They Have Cast on the Waters Comes Floating Back: Gordon Shadrach & Kachelle Knowles

Written by Byron Armstrong

“People who treat other people as less than human must not be surprised when the bread they have cast on the waters comes floating back to them, poisoned.”

-James Baldwin, “No Name in the Street”

Diaspora refers to the dispersion, scattering, or migration of a people living in different lands. For the Afro-Caribbean diaspora, the word suggests so much more. Lived differences as vast as shared realities are narrow, like shards of glass, a testament to the structure that once preceded it. They are scattered across distances spanning miles, centuries, and sometimes just the length of a conversation. Gazing into broken glass has the same effect as staring into water troubled by a heavy stone dropped onto its surface. This is a diaspora for Black people. A ripple effect of refracted selves where the water breaks — was broken — by outside influence. We hold this stone deep within us, even as the water calms and memory fades. Submerged, but still felt. Blackness is not a monolith and yet the social construct of race and the systems built to enforce it were replicated across colonies. This replication has led to a hive-mind understanding of Black folk across the globe. An instinctual knowing of place within the plantation hierarchies of a white supremacist fever dream; a narcolepsy of spirit that Black folks have been trying to wake their captors from as the house they share burns down around them. This house of horrors, according to Baldwin in “The Fire Next Time”, is one that he questioned the wisdom of integrating into.

Although Black women were not excluded from dehumanization through over-sexualization, Black males also faced the perception of having inhuman strength to carry out their desires, specifically against white women, if unchecked. In addition to the lie that Black males were also lazy if not forced into labour, propaganda around their oversexed, violent natures gave the state the right to police, maim, and kill them with impunity. This legacy follows us today in the statistics of disproportionate deaths at the hands of police, and the lynch mob mentality of private citizens taking it upon themselves to levy justice against activity deemed suspicious. Allegedly whistling at a white woman (Emmet Till - U.S.), jogging down the street (Ahmaud Arbery - U.S.), driving with your family (Philando Castile - U.S.), sleeping in your car (Jay Anderson Jr. - U.S.), experiencing a mental health crisis (Andrew Loku - Canada), (Clive Mensah - Canada), (Jean-René Junior Olivier - Canada), (Abdirahman Abdi - Canada), walking home (Trayvon Martin - U.S.), standing in a group (Neptune Four - Canada), taking a cab (Mark Duggan - UK), driving away from the police (Chris Kabba - UK), have been any number of “reasons” for Black males to die across the diaspora. “When the Bread They Have Cast on the Waters Comes Floating Back” interrogates how these aforementioned refracted selves are but a ripple effect of colonization and white supremacy. Borrowed from the title of Baldwin’s nonfiction work entitled “No Name in The Street”, this Transatlantic collaboration between artists Gordon Shadrach (Toronto, Canada) and Kachelle Knowles (Nassau, Bahamas) is a dialogue between diaspora. Revolving around themes of identity and representation, it celebrates the Black male by disrupting colonial narratives and the distorted reflections it creates through figurative portraiture. It’s in this spirit that gallery United Contemporary (Toronto, Canada) and The D’Aguilar Foundation (Nassau, Bahamas) endeavour to foster a dialogue between their distinctive practices through this duo-exhibition.

The term “Commonwealth” feels like a misnomer in the case of the Caribbean. What wealth is distributed evenly to common folk on the islands? Even the effects of climate change propagated by the Global North, disproportionately affect nations in the Global South. That a society with heavy reliance on the comfort of tourists would reinforce colonized ways of thinking in its populace in school is unsurprising. Knowles' School Boy Series: He's a Runner, He's a Track Star (2023) addresses how Black male physicality can be rewarded over intellectual pursuits, indirectly playing to eugenic tropes about Black IQ and the heightened athleticism of Black people.

“In the traditional school system, glory is found either in academics or sports. Those who are unable to succeed in their grades but excel greatly in sports turn into school heroes, and this tends to be more valued for men. Their ability as physically fit runners who place ( 1,2,3 and nothing else matters) are seen as popular and desired, so long as they come in first, second or at very least third place, and they now are more worthy than they ever could be.”

-Kachelle Knowles

Knowles employs materials like graphite, coloured pencils, collage, marker, ink, gold leaf, and acrylic gemstones on toned paper to decorate a young sprinter in the style of a gladiator. An emerald-patterned shirt speaks to the colour scheme used in Knowles’ high school. Within the school, there were four “houses”, one of which (labelled “Dolphins”) was coloured green and was considered the most prominent house. Demi-godlike in his presence, the figure is adorned with a variety of gold medals representing his elevated status to his peers. What is the status based on? Black physical power earns praise in controlled circumstances and provokes fear outside of them. For proof, look no further than Muhammad Ali, stripped of his title in 1966 after refusing to fight in Vietnam on religious grounds. Tommie Smith and John Carlos were expelled from the 1968 US Olympic team and faced homelessness and derision for raising their fists in solidarity with the Black Power movement on the Olympic podium. Colin Kaepernick was unofficially blacklisted from the NFL after taking a knee in 2016 during the national anthem to protest and speak out against police brutality and racial injustice. The message is clear. Run, jump, lift, throw, entertain and you will be rewarded. But whatever you do, don’t think. Don’t emote. Don’t vocalize dissent.

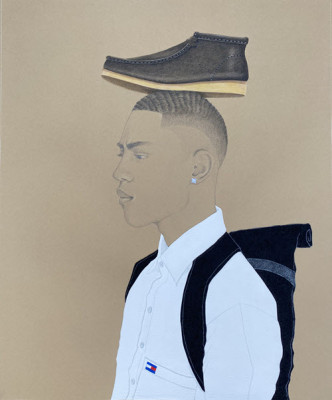

In Take the Headboy Out of Your CV (2023), Knowles uses many of the same materials to continue the conversation about how society values Black boys. It is a recognition of the boy who is labelled “too smart” for their own good or “too interested” in their appearance. Conceived as an over-the-top version of the Bahamian school uniform, the pinned broaches and plaid scarf flourish also speak to the right of Black boys to express their individuality without the scrutiny of gender performance or the policing of Black hair —afros and facial hair often considered uncouth and indicative of lower class. As Baldwin said in “No Name in The Street”, “To be liberated from the stigma of Blackness by embracing it is to cease, forever, one’s interior agreement and collaboration with the authors of one’s degradation.”

Except for what lies on the surface, Gordon Shadrach could be seen as very different from his colleague. Age, gender, and geography should all point to lived experiences that are opposite to each other. However, Shadrach’s work intersects and overlaps like the long-lost piece of a puzzle found on the opposite end of the same room, where the presence of Black people — whether in The Bahamas or Canada — is least threatening when invisible or removed.

“So in our conversations, we were talking about how tourists feel uncomfortable when they see Black male Bahamians, in particular, actually enjoying the same spaces with them.

Experiencing that differently in Canada, for me it became about this idea of exploring black boy joy in public spaces as an act of rebellion.”

-Gordon Shadrach

In his Fence Series (2023) Shadrach’s fences become an allegorical and literal barrier that thwarts Black joy. His paintings show the diminishment of barriers represented by shadows cast over Black figures. In Armour (2023), a dreadlocked male stands with his hands clasping the fence with an expression of longing. The barrier to his happiness is apparent, the shadows marking his face could just as easily be the long shadow cast by white supremacy and systemic oppression.

“Although we've been told that the barriers have come down and we're free to be ourselves, there’s still this scar tissue, which is the long-lasting effects of systemic racism, that impacts our freedom just to live our lives.”

-Gordon Shadrach

Emerge (2023) reimagines the fence as having less power over the intended, with an opening where the Black male figure’s face sits. Even with the hole in the fence, there’s still a noticeable crisscrossing of shadow across the figure's face. As a small piece of the barrier dissipates, it leaves behind lines, like scar tissue, on the face of the figure. Perhaps, even after barriers come down, there’s still damage left behind and more barriers to remove. Shadrach’s paintings acknowledge the bypassing of barriers Black people have worked hard to secure, as well as the impact of the psychological, emotional, and at times, the physical toll it has taken to get there.

Knowles and Shadrach are shining a light on identity, representation, gender, and the impact of colonization, enslavement, and anti-Black racism on our collective values and perceptions. Although expressed differently, these themes are universal to the Afro-Caribbean diaspora. As such, they are successfully adding their voices to the Black experience in visual art.